Part 1: The modeling mindset: thinking beyond the form

If you’re reading this, you probably grasp the fundamentals of openEHR. If not, check out my first post – The ultimate openEHR foundational guide. If you do understand the basics – congratulations – because it’s a significant first step. But it’s one thing to understand the theory and another to put it into practice. Clinical modeling is where you translate that abstract knowledge into a working, real-world system and make the magic happen. This post is your comprehensive guide to practically applying your openEHR knowledge by modeling clinical data for real-life scenarios.

What is clinical data modeling?

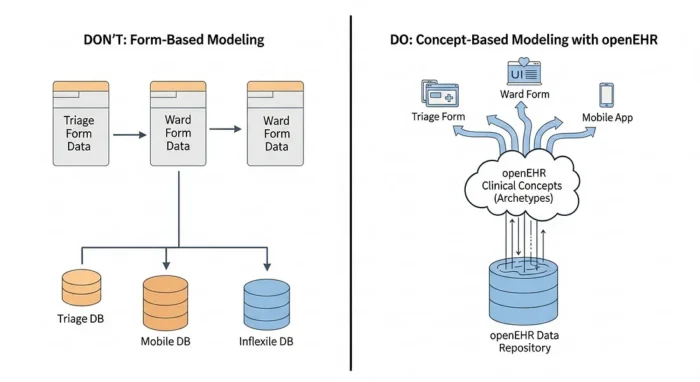

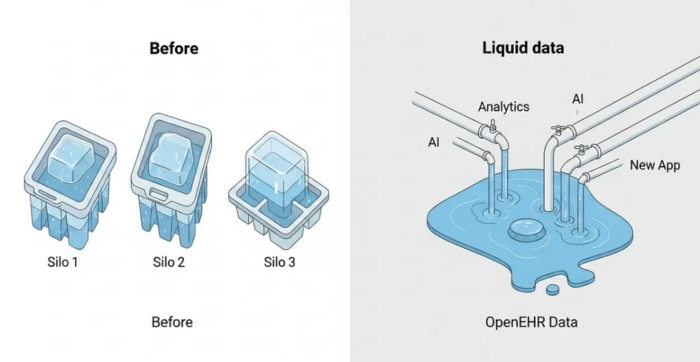

Let’s start with a clear definition: clinical data modeling in openEHR is the process of defining structured, interoperable, and semantically rich representations of clinical information. Unlike traditional database design that focuses on tables and columns (and is often tied to one application), openEHR modeling focuses on expressing clinical meaning through standardised models. The goal is to create data that can be consistently captured, exchanged, queried and reused across all systems, forever.

The aim isn’t just to store data; it’s to ensure the meaning behind the data remains intact over time, regardless of changes in technology, vendors or interfaces. Proper modeling results in data that is future-proof, semantically computable, clinically safe, and suitable for long-term electronic health record continuity.

The modeling mindset: a new way of thinking

This is the most crucial part. To succeed in openEHR, you need to shift your mindset a little… Clinical modeling requires both technical and clinical reasoning. You must find a perfect balance between the two. This mindset is fundamentally different from that of a software engineer who might design models based strictly on application logic or UI needs. In openEHR, the priority is long-term semantic correctness, not short-term application convenience.

Key mental shifts include:

- Model clinical concepts, not system forms or UI widgets.

- Aim for reusability, not local or project-specific shortcuts.

- Use coded, standard terminologies where possible instead of free text.

- Expect evolution and model in ways that allow extension, not replacement.

- Align models to real clinical practice, not institutional data entry habits.

This mindset ensures that clinical data remains valid and interpretable decades after its initial capture, independent of system vendors or UI changes. These points might seem vague at first, but don’t worry: you’ll see references to these mindset shifts as we continue, and it will all become much clearer.

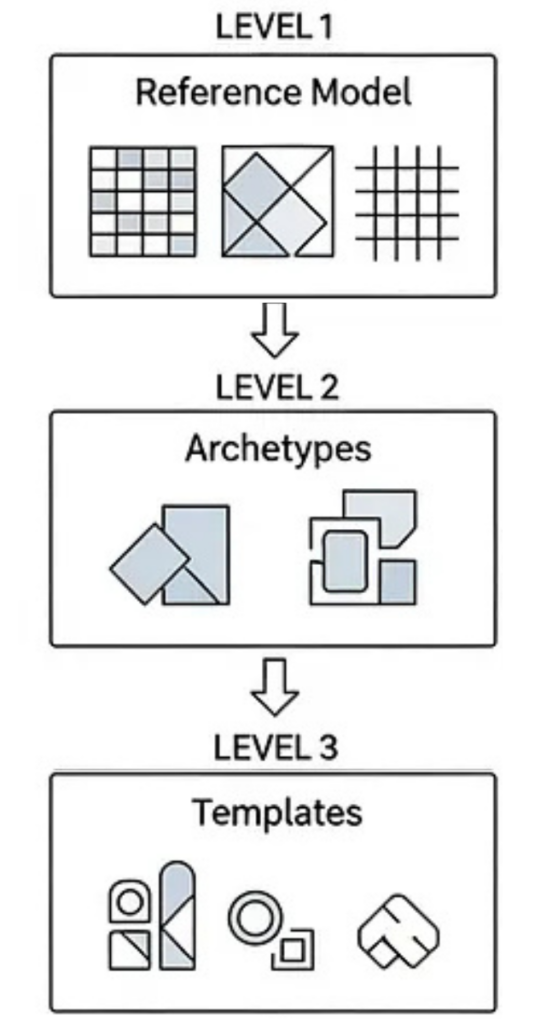

Part 2: The core architecture: the “three-layer” model

Let’s briefly circle back to the fundamental building blocks of openEHR. Modeling is separated into three distinct, interlinked layers:

The Reference Model: (RM)

This is the stable, technical foundation. The RM defines the generic building blocks and datatypes – the “atoms” of the system, like Compositions, Observations, Instructions, Clusters and Elements. It also defines the data types they can hold, such as DV_TEXT, DV_CODED_TEXT, DV_QUANTITY, and DV_DATE_TIME. The Reference Model never changes based on local clinical workflows. It’s the universal grammar of health data.

Archetypes (AT)

These are the ‘clinical concepts.’ Archetypes represent universal, reusable definitions for concepts like “Blood Pressure,” “Allergy,” “Problem/Diagnosis,” or “Medication Order.” They are designed by clinical experts to describe the maximum semantic scope of a concept. A good archetype is intended to be reusable across different domains, institutions and even countries.

Templates (OPT)

These are the “implementation.” Templates are where you bring it all together for a specific, local use case.

You can create a template by combining one or more archetypes and then applying local constraints. For example, you might take the universal “Blood Pressure” archetype and create a template for your “ER Triage” form by:

- Hiding elements you don’t need (e.g., “location of cuff”).

- Restricting value sets (e.g., “body position” can only be “sitting” or “lying”).

- Specifying required fields.

This process produces the final, deployable Operational Template (OPT) that an application can understand and use. Together, these layers give you stability (from the RM), clinical reusability (from Archetypes), and local flexibility (from Templates) without compromising interoperability.

Modeler’s pro-tip: You must keep these three layers mentally separate. Understanding their distinct roles is the key to making the right decisions when you’re selecting a Reference Model, searching for archetypes, and building templates.

Your modeling toolkit

Now we’ve covered the mindset and the architecture, the rest of this post is the “how-to.” To follow along, you’ll want to have these tools handy. (I’ll be referencing them from here on…)

- The Clinical Knowledge Manager (CKM): This is the global library of published archetypes. Your first stop, always.

- An Archetype Editor (AE): For viewing or creating new archetypes.

- A Template Designer (TD): For building your templates.

You can get a free, web-based Archetype Editor and Template Designer by using Better’s Archetype Designer suite.

All set? Great. Now let’s begin the real work.

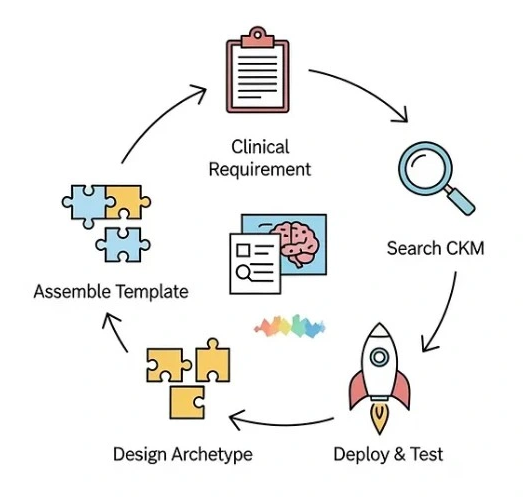

Part 3: The modeler’s workflow: from concept to deployment

This is the core of the work. Modeling isn’t just one task; it’s a step-by-step process that moves from a clinical idea to a usable, deployable asset.

Step 1: Start with clinical requirements, not code

Before you ever open a modeling tool, you must do a thorough domain analysis. This is the single most important step to ensure your model aligns with real clinical needs, not just technical assumptions.

The analysis step should include:

- Understanding the workflow: Where does this data come from?

- Defining the user: Who records the data and in what context?

- Clarifying the “why”: Why is this data needed, and how will it be used?

- Identifying data points: What is mandatory vs. optional?

- Reviewing sources: Check existing clinical documents, guidelines, and terminology libraries.

- Consulting experts: Talk to clinicians, nurses, or domain specialists.

The output of this phase should be a structured requirements sheet. This document, listing data elements, definitions, units, terminology sources, and rules, becomes your blueprint.

Modeler’s pro-tip: This analysis also helps you choose the right Reference Model (RM) class for your main concept. Is it a clinical document or form (COMPOSITION)? A set of measurements (OBSERVATION)? A clinical conclusion like a diagnosis (EVALUATION)? Getting this right from the start is essential.

Step 2: Search before you build (the CKM is your best friend)

Now that you have your requirements, your first action is not to build. It’s to search. openEHR’s power comes from reuse. The Clinical Knowledge Manager (CKM) – powered by openEHR’s industry partner Ocean Health Systems – is the global repository of peer-reviewed, vetted archetypes, so you should always check here first. Reusing an existing archetype ensures semantic interoperability, reduces your modeling effort, improves safety and aligns your work with international best practices. So…

- Search the CKM using both clinical and lay terminology.

- Read the archetype’s “description,” “use,” and “misuse” notes.

- Review the node structures and value definitions.

- Check its status (e.g., Draft, Team Review, Published).

- Ensure it aligns with your clinical requirements.

The 80% Rule: If an archetype fulfills 80–90% of your requirements, it’s almost always better to reuse it and handle the minor differences at the template level (which we’ll cover later).

Step 3: When (and how) to create a new archetype

Let’s be clear: it is almost guaranteed that most of the archetypes you need already exist in the CKM. A vast amount of clinical expertise and countless use cases have likely covered your workflow. You will only need to create a new archetype in rare or highly specific cases, so you should only create a new one when no existing model captures the concept in a clinically sound and reusable way.

Before creating one, ask yourself these questions:

- Can I represent this by combining existing archetypes in a template?

- Can I create a specialisation of an existing archetype?

- Can a simple template constraint achieve my requirement?

If the answer to all three is “no,” then you can go ahead and create a new archetype.

The science of archetype design

This is the beginning of semantic modeling itself. When you design a new archetype, you are defining a new, reusable clinical concept for the world.

Key design principles:

- Choose the correct Entry class: This is critical for clinical intent.

- Observation: For measured or reported values (e.g., blood pressure, symptom).

- Evaluation: For clinician-judged conclusions (e.g., diagnosis, risk assessment).

- Instruction: For planned clinical actions (e.g., medication order, referral).

- Action: For executed clinical actions (e.g., procedure was performed).

2. Organise data logically: Structure the data to reflect clinical reasoning, not the sequence of a specific UI form.

3. Use the correct data type:

- DV_QUANTITY for numeric values with units.

- DV_CODED_TEXT for coded values linked to terminologies (like SNOMED CT).

- DV_DATE_TIME or DV_DURATION for time-related data.

- DV_BOOLEAN only when a binary yes/no is clinically accurate.

- DV_TEXT only for narratives that cannot be safely and structurally coded.

4. Consider repeatability: Use CLUSTERs to group related elements (like the ‘systolic’ and ‘diastolic’ in a blood pressure). Use occurrences and cardinality to specify what is required, optional, or can be repeated.

A well-designed archetype clearly reflects its clinical meaning, independent of any single application.

Step 4: Designing your archetype

As you design, you’re not just adding nodes, but rather you’re applying rules. This is where constraints and terminology come in.

Applying constraints: cardinality, occurrences and value rules

Constraints define what is mandatory, optional, repeatable, or restricted within your model. They are essential for patient safety, data quality, and computability.

Three major constraint areas must be configured carefully:

- Occurrences: Defines if an element is required or optional (e.g., 1..1 for mandatory, 0..1 for optional, 0..* for repeatable).

- Cardinality: Used primarily for clusters and repeating elements to specify how many instances are allowed (e.g., “allow 1 to 5 instances of this group”).

- Value Constraints: This is where you control the data itself. You can set numeric ranges (e.g., 0..300 mmHg), restrict allowed terminologies, fix units (e.g., “must be ‘°C’”), or list the specific coded values allowed.

Modeler’s pro-Tip: Mandatory fields should only be enforced if clinically necessary, not for administrative convenience.

Correct constraints strike a balance between safety and flexibility. Over-constraining leads to workflow pain; under-constraining produces weak, unusable data.

Binding semantics: the role of clinical terminology

This is what makes your model ‘semantic.’ Terminology binding ensures that data captured with your archetype can be interpreted consistently across systems, regions, and time, so while the archetype defines the structure (e.g., “a diagnosis name”), terminology binding connects that data point to a recognised external code system like SNOMED CT, LOINC, ICD, or RxNorm.

There are two main types of binding:

- Term Binding: Links an archetype node (like the “Diagnosis name” node itself) to a standard terminology concept (like the SNOMED CT concept for “Diagnosis”).

- Value Set Binding: Restricts the possible values for a coded data point to a specific list (e.g., the “body position” node can only be filled with codes from a specific LOINC value set for “sitting,” “standing,” or “lying”).

Modeling without terminology binding introduces ambiguity and limits all future use for analytics or decision support.

Finalising the archetype: versioning and governance

You’re almost finished your archetype, but remember: archetypes are long-lived knowledge assets, not disposable project files. They must follow a controlled governance process and with that in mind, openEHR has built-in versioning to allow for safe updates while maintaining clinical and legal traceability. Every archetype carries metadata documenting its authors, contributors, purpose, review state and change log.

Good governance involves:

- Adhering to semantic versioning (major, minor, and patch changes).

- Running peer and clinical review cycles.

- Avoiding “breaking changes” that would invalidate historical data.

- Publishing through a recognised governance body or CKM.

Collaboration is key here: archetype work should never be a single-person activity, especially when it’s intended for reuse in a production system.

Step 5: The ‘art’ of templates: from blueprint to application

Now we move from the universal to the specific. While archetypes are designed to be maximal and reusable (e.g., the complete ‘Blood Pressure’ concept), templates are what you create for a specific, local use case. This is where you, as the modeler, tailor the archetypes for a real-world workflow, such as a “Triage Form,” an “In-Patient Discharge Summary,” or a specific app feature.

In your Template Designer, you will:

- Combine multiple archetypes: Your “Discharge Summary” template might combine archetypes for Problem/Diagnosis, Medication Order, and Follow-up Instruction.

- Constrain the nodes: You’ll hide unwanted elements, set default units (e.g., lock in ‘kg’ for weight), and restrict value sets (e.g., my clinic’s list of ‘discharge reasons’).

- Set rules: You’ll define what is mandatory (1..1) or optional (0..1) for this specific form.

- Localise: You can even change labels (e.g., rename “Synopsis” to “Summary”) to match your organisation’s language.

The final, exported file is called an Operational Template (OPT). This OPT is the single, deployable, machine-readable artifact that defines exactly what your system will accept, store, and validate. It’s the ultimate bridge between your clinical model and the running software.

Step 6: Deploying and testing your template

This step marks the transition from modeling theory to runtime implementation.

Your deployment workflow typically looks like this:

- Export: You export your finished template as an .opt file from the modeling tool.

- Upload: You upload this OPT to your openEHR server (like EHRbase or the Better Platform) via its API or admin console.

- Register: The server registers the template, gives it a unique ID, and now understands this new data structure.

- Implement: Your applications can now use this template_id to create valid COMPOSITION instances (i.e., save real patient data). The system can even auto-generate UIs, forms, and JSON schemas directly from the OPT, drastically speeding up development.

But a model is only as good as its real-world usability. The moment your OPT is deployed, you must test it with example data instances (usually formatted as JSON or XML).

The goals of testing are to:

- Confirm the logical flow and clinical usability.

- Ensure all your constraints (mandatory fields, value sets, ranges) behave as expected.

- Check how missing, optional, or repeating data is handled.

- Verify that the resulting data structure is easy to query using AQL (Archetype Query Language).

You must run both positive (“good data”) and negative (“bad data”) tests. Clinical modeling is safety-critical. When you find issues (and you will) you simply return to the Template Designer, refine the template, and redeploy the new version. Iteration is a normal and essential part of the process.

Part 4: From theory to practice: pitfalls & best practices

You now have the complete workflow, from concept to deployment. As you start, it’s helpful to learn from those who have gone before you. Modeling is a discipline, and a few common pitfalls can reduce your data’s usability or create future maintenance problems.

Common modeling mistakes (and how to avoid them)

Many early adopters make these errors. Watch out for them!

- Modeling the form, not the concept: Building a model that looks exactly like an old paper form, rather than modeling the clinical concept that you’re trying to capture.

- Creating new archetypes too easily: Ignoring the CKM or the 80% rule and creating a custom archetype when a reusable one already exists. This breaks interoperability.

- Over-constraining: Making too many fields mandatory (1..1) for administrative reasons, which frustrates clinicians and doesn’t reflect real-world practice.

- Using free text everywhere: Using DV_TEXT for data that should be coded (like a diagnosis or a medication), which makes the data impossible to query or analyze.

- Misusing entry types: Forgetting the basic Entry classes (e.g., using an OBSERVATION to record a DIAGNOSIS, which should be an EVALUATION).

- Ignoring terminology: Skipping the terminology binding step, leaving your data semantically ambiguous.

The avoidance strategy is simple: stick to the CKM guidance, involve clinicians in every step, follow established patterns and always model for the long-term life of the data, not short-term convenience.

Best practices for sustainable, reusable models

Good openEHR modeling produces a permanent asset, not a temporary deliverable, so to create models that scale across vendors, countries and decades, follow these practices:

- Start with domain research, not tooling.

- Reuse archetypes whenever possible.

- Follow established modeling patterns from the CKM.

- Apply constraints only where there is clear clinical justification.

- Use controlled terminologies (like SNOMED CT) to improve semantic precision.

- Validate everything with real example data and clinician reviews.

- Document your intent, sources, and assumptions.

- Plan for governance, versioning, and (if possible) sharing your models with the community.

Your model must remain useful long after the application code evolves, the interfaces change, or the national standards are updated.

Part 5: Conclusion: your journey as a modeler

Clinical data modeling in openEHR is both an engineering discipline and a clinical knowledge discipline. It demands a structured mindset, a rigorous methodology and a respect for global standards.

When done correctly, the result is an interoperable, future-proof, and clinically meaningful dataset that can power analytics, AI, longitudinal care and national-scale digital health solutions. Strong modeling is one of the most important foundational skills in digital health, it is where clinical safety and technical architecture meet.

Your next steps

Your journey doesn’t end here and the next steps are all about practice:

- Start practicing with real-world clinical scenarios.

- Join the CKM discussions and reviews to see how experts think.

- Deploy an OPT on a sandbox server (like a test instance of EHRbase).

- Write example data instances and try to query them with AQL.

- Contribute back to the community by suggesting improvements to archetypes.

In essence, understanding how to model clinical data comes with practice and experience; but I promise that at some point, it’ll become muscle memory. Happy building!

Anselm Iwuanyanwu is an Interoperability Lead and software engineer passionate about future-proof health data. With a unique background in both clinical pharmacy and full-stack development, he specialises in designing and building scalable systems using openEHR and FHIR standards. He is dedicated to advancing semantic interoperability in the global digital health landscape. Follow him on Linkedin

Leave a Reply